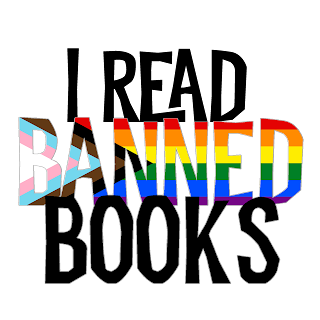

I Read Banned Books

I sat through a loooong school board meeting

last week because a few angry parents had called for a book to be banned. The

book in question was written by a transgender author, and the protagonist was an

eleven-year-old trans character. I mention this only because 41% of the more than 1600 books that were banned in the U.S. last year involved LGBTQ+ authors,

protagonists, or main characters, and because the PVPUSD board room was packed with LGBTQ+ community and allies.

The call to ban the book was not an agenda item, and the district had publicly

said they were not considering banning that or any book, so the 50+ speakers

and more than a hundred other allies were there to send a clear message to the

district. We value diversity in our books, we need representation of the LGBTQ+

community not only for the people who identify as such but for everyone, and

perhaps most importantly, the message was clearly delivered that a few loud,

angry people do not have the right to dictate what anyone else can or can’t

read.

Period.

The middle-grade award-winning book was about gender, but it could have been a book by an author of color (40% of all banned books last year were by or about people of color), or one that no longer fits the language and sensitivity of the times (Dr. Seuss and Huckleberry Finn, for example). The fact that a teacher read it out loud to her class doesn’t even matter because it’s on the California Department of Education’s recommended-reading list. What’s at stake looks complicated when people think about “parental rights” and “what’s appropriate for children,” but it’s actually incredibly simple. The First Amendment has granted the rights of freedom of expression to all people in the United States, the Fourteenth Amendment extended that right to guarantee that State and Local government cannot infringe on it, a 1969 case heard by the Supreme Court determined that “neither teachers nor students shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” and in 1982, they extended those protections to students again by ruling against the removal of books by school boards.

All of that is to say that my right, and my children’s right to read whatever we want to read is guaranteed by law.

“But what about the children?” they say.

The

students who spoke publicly at the PVPUSD board meeting talked overwhelmingly about finding empathy and identity in books that focused

on inclusion and diversity. They showed the vandalized signs for the weekly

Queer Social Club meetings, and spoke about what it meant to feel safe and part

of a community. They talked about the amazing teachers they’d had, the things

that made them feel understood, and the mental health dangers of feeling alone

and unsupported. Books can connect us, they said. They can show us what it

feels like to be Black or Trans or gay when you’re not, and they can make us

feel seen and heard when the world feels overwhelmingly different than you.

“But my

rights as a parent…” they say.

ChatGPT's answer to that was excellent. “While there may be some books that are controversial or

objectionable, schools can address this issue by providing guidance on how to

approach challenging material and fostering discussions around difficult topics.

Removing books altogether would deprive students of the opportunity to engage

with diverse perspectives and develop their own opinions and beliefs.”

“Sexual

content isn’t appropriate for children,” they argue.

First

of all, I'm going to say this out loud because the book in question in my district was

about a trans kid wrestling with their gender identity. Gender isn’t sex. And I'll say it again for the people in the back. GENDER AND SEX ARE NOT THE SAME THING. Collapsing them makes people sound ignorant.

Secondly,

different people have different ideas about what is considered explicit, and

what is “appropriate” for kids. Ultimately, it’s up to a library or a school

district to determine which books to include

in their collections and curriculum—with inclusion being the operative term.

Inclusion

and representation are now the law in California Education Code. The focus on mental

and emotional wellness since the pandemic continues to stress that feeling part

of a community is vital to young people, and communities come in all colors,

shapes, sizes, and identities. The Fair Act mandates that governing

boards in school districts include curriculums and materials that accurately

portray the cultural and racial diversity of our society, and a new bill is now

in committee that prohibits school boards from banning (emphasis mine) any curriculum or learning materials without State approval

(AB 1078).

Banning books doesn’t “protect

the children,” it harms them. It limits their abilities to become critical

thinkers, to become empathetic, informed, educated

human beings.

Our ability to consider emotions and

circumstances, to draw connections while reciting facts and analyzing data is

what makes us critical thinkers. Allowing students to read and learn about the

world, their histories, each other, and themselves with guidance from trained

educators, alongside parents who read and discuss the books with their children—that

is the basis for learning to be a critical thinker, and arguably, what produces

people who understand all the ways in which our differences connect us to our communities and to the world around us.

I made friends at that board meeting

last week, and I know a little more about some of the people I see every day

because they were there. I sat in a room full of people who believe in

inclusion, who believe that representation is important, and that freedom means

being able to read what you want, love who you want, and be who you are. Book banning is not the

freedom to choose what your child reads. It’s taking freedom away from everyone

else because you’ve decided you know better.

I’ve read thousands of books in my life,

and I know this: every person is the hero of their own story, and the more books I

read, the more ways I find to connect with those heroes, fictional and real.

And like the books I read, my story is so much richer, better, and more

interesting because it’s full of diverse characters, inclusive of experiences I’ve

never had, and representative of the world in which we all live.

P.S. I made the graphic because I'm fired up about this. I turned it into a t-shirt, and if you see me at a book event you can pick up a sticker, but feel free to use it however you like.